Despite his tragically early death, Derrick Harris (1919-1960) was an important illustrator of the mid-20th century. Ruth Prickett asks his widow about the man and the artist.

Derrick Harris is not a household name, yet he has been described by wood engraver Simon Brett as “the missing link in the history of British graphic art in the 20th century”. So why has he been neglected and is anything being done to restore his reputation?

One major reason for his lack of fame today is that his suicide when he was just 40 prevented him from ever realising many of the achievements that his talent and early commissions promised. This is not to say that he was not recognised in his lifetime. He was chairman of the illustrators’ section of the Society of Industrial Artists between Edward Ardizzone and Eric Fraser and was the only wood-engraver whose work was featured at the Festival of Britain in 1951. According to Brett, his death “left the public profile of wood-engraving in the hands of more conservative practitioners”.

Born in Chislehurst, Kent, Harris grew up in Sussex and then studied at the Central School of Art under John Farleigh. When the war broke out he registered as a conscientious objector and was assigned to the heavy rescue depot in Berkeley Square, London.

“Heavy rescue was actually very dangerous in the Blitz,” recalls his widow Maria de Botello(formerly Mavis Harris). “He was attending art school during the day and then doing the 4 -12 shift portering at University College Hospital. That’s how we met. I was nursing at the time. It was a cold night and I sent down for a bucket of coal. Derrick brought it up and the following night I sent down for more coal.”

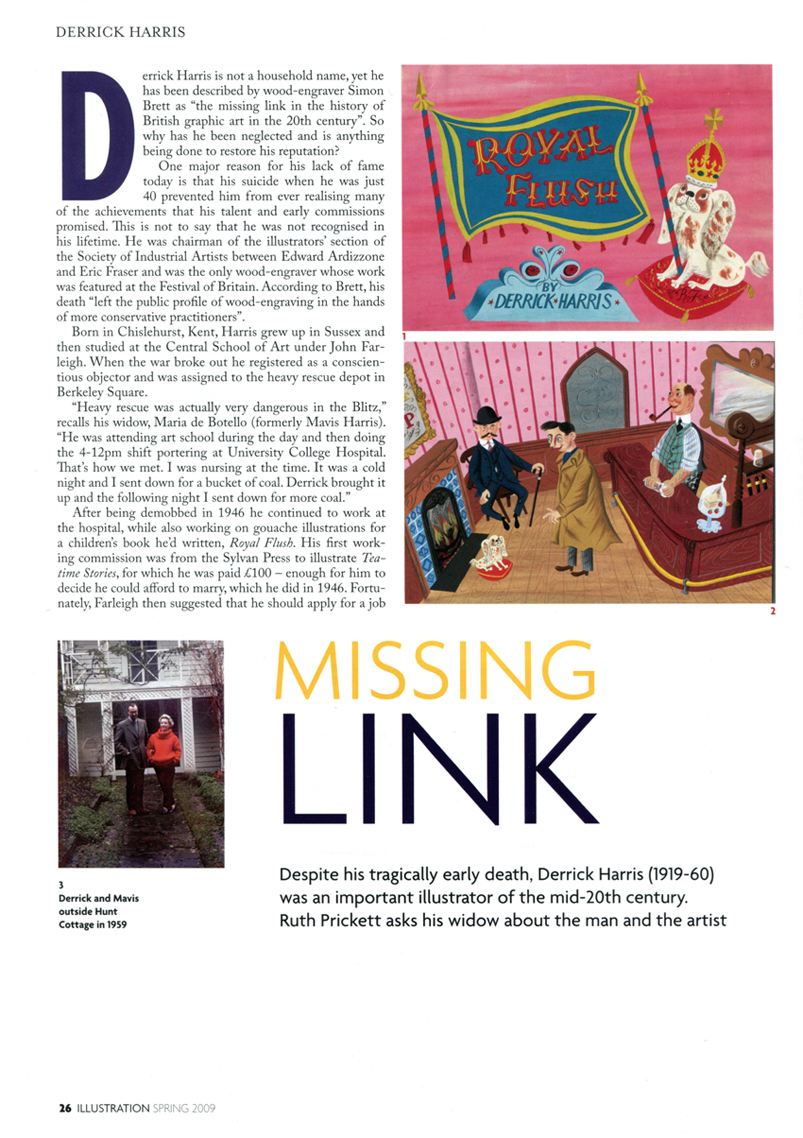

After being demobbed in 1946 he continued to work at the hospital, while also working on gouache illustrations for a children’s book he’d written, Royal Flush. His first working commission was from the Sylvian Press to illustrate Teatime Stories, for which he was paid £100 – enough for him to decide he could afford to marry, which he did in 1946. Fortunately, Farleigh then suggested that he should apply for a job teaching illustration and wood-engraving at Kingston, which would ensure a steady income.

“John later told me that Derrick was unique because lots of young people were wanting to study wood-engraving and book illustration, but only one in a million of them was an artist – and that Derrick was that artist,” says Botello.

Fortune also favoured the couple when they had the luck of being offered Hunt Cottage in the Vale of Health, Hampstead, to rent. The cottage had once belonged to Leigh Hunt and had often hosted gatherings that included the poets Keats, Shelley and Byron. By the time the Harrises moved in it was run down, but Botello embarked upon what she now calls “my first big restoration job”. She had also attended art school, specializing in cutting and needlework, and put into practice skills that later developed into a career in fashion magazines and finally tapestry and textile conservation.

The couple shared an interest British folk art and were ahead of the fashion for cheap antique furniture and traditional decorative elements such as Staffordshire figures, which became far more common in the 1950s. Their picturesque home later featured in articles in the 1950swhen Harris began to gain fame as an illustrator for the Radio Times, The Listener Magazine, Penguin Books including Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited and Scoop, and Folio Society books including Joseph Andrews (1953), Humphrey Clinker (1955) and Tom Jones (1959).

R D Usherwood, then art editor of the Radio Times, wrote, “Harris was a wood-engraver with a particular and invaluable gift. His work had something of the gusto of the early 19th century.” He published Harris’s engraving “Germany Today: A Series of Talks”, showing a two-headed phoenix emerging from a burning swastika, in his book Drawing for Radio Times (Bodley Head, 1961). It was to be the last that Harris produced for the magazine before his death.

“His cutting is so crisp that it reproduces very well,” Usherwood wrote. “In general, fine wood-engraving loses that quality of its finer lines in newspaper printing… Few engravers work as quickly and surely as Harris.”

Oddly, despite his fame as a wood-engraver and the fact that he went on to teach this medium not only at Kingston, but also at Reigate and Hornsey Schools of Art, Harris initially preferred to work in colour. Royal Flush remains unpublished, but the original vibrant gouache illustrations, which are still in Botello’s collection, show his early inspirations. She explains that the switch was purely practical.

“One of the reasons why Derrick took to wood engraving was because after the war colour was just far too expensive,” she says. “So he went back to basics and found he could do everything right up to the point it arrived at the printers, which made the whole process much cheaper.”

And publishers appreciated this, as well as the artistic merit of his work. In addition to his work for Penguin and the Folio Society, he undertook commissions for the Golden Cockerel Press, advertising (including Shippam’s Paste, Savora Sauce and Ribena), women’s magazines, as well as a variety of work for the Ceylon Tea Centre, Lower Regent Street, and a series of nursery rhyme illustrations for Air India. His wood-engravings for the Festival of Britain in 1951 were illustrations of “The Modern Duck’ and “The Modern Hen”, which were blown up and shown in the agricultural section.

At home, the Harrises moved in circles that included many of the leading illustrators of the day: Faith Jacques and Robin Jacques, Barbara Jones, Dorothy Braby, Ardizzone and Lynton Lamb, Hunt Cottage had been brought back to life again as the centre of a buzzing artistic circle.

In style, Harris’s work clearly drew on the 18th and 19th century traditions, but had a life and sparkle that offered entertainment, satire and fun at a time when so much of British life was austere and impoverished. Brett describes him as having a unique style that sat somewhere between Rowland Emmett and Edward Bawden.

His growing prestige was reflected by his appointment to the board of the Crafts Council and an invitation to become chairman of the illustrator’s section of the Society of Industrial Artists (SIA). Ardizzone, in his obituary of Harris said of him that he was “the perfect secretary of out illustrators’ committee. Quite unobtrusively he did all the work and shamed me, his chairman, who did none. But when it was his turn to become chairman we all knew at once that here was a man who could do a job better and more conscientiously than the rest of us.”

Despite the joy evident in his illustrations, Harris’s life took a downward turn when the owner of Hunt Cottage decided he wanted it back. The Harrises had been there for over 14 years and had invested huge amounts of energy and love in the place. Harris accepted this – Botello says he said they had a “moral” duty to leave even though friends said they had legal rights as long-tern tenants and should consult a solicitor – but the loss affected him terribly and Botello is sure that it contributed indirectly to his death 18 months later.

“We left the cottage 10 days after we were told the owner wanted it back and Derrick destroyed a lot of work before we left. I think that’s when we lost all his original images for Roderick Random (commissioned by the Folio Society but passed to Frank Martin when Harris was asked to do Joseph Andrews). He also had a beautiful gouache of gypsies and when we left the cottage I heard banging and found him breaking it up. I was upset and angry about it, but had no idea why he did it.” Botello says.

Now homeless and camping with friends, Harris was invited to visit New York for an SIA exhibition. “We were given a special allowance from the Bank of England to attend and the American artists were unbelievably welcoming,” Botello recalls. “We met people including Joseph Loewe and Saul Bass and they suggested we should move out there.”

Botello used her share of the money to travel by Greyhound Bus around the US and says she “fell in love with America”. Harris had to return to London for an exhibition of his Folio Society work on Tom Jones. In his last letter to her, Harris wrote:” Go to America if you can.” After his death she took his advice and got a job making props for the photographer Irving Penn in New York before continuing to travel down to Mexico.

Despite the success and exhibitions, and the fact that they found a new flat in Queen Anne Street, Harris was deeply depressed. He attempted suicide while Botello was visiting her parents shortly before Christmas 1959, but his note was found in time by the cleaning lady. He was then put under medical supervision but made better plans for his second, successful, attempt. He told his wife he would be dining with his head of department at Hornsey and, after meeting a friend for a drink after work, he went to a room he had rented in Kensal Green and turned on the gas.

His friends and family were astonished and deeply shocked – all the more so because there seemed no reason for his depression. “Ted Ardizzone wrote a lovely obituary,” Botello says. “Fortunately I was established in the world of fashion magazines by then and this kept me going. I just kept working.”

Brett agrees that the loss of the cottage had a profound effect on Harris, but speculates that this loss exposed other insecurities – professional, artistic and sexual – that he had been burying. He points out that while Botello had been excited by the opportunities of America, Harris may have also felt threatened and uncertain about new developments and artistic trends he saw there. Furthermore, he had unresolved personal problems: he was bisexual at a time when homosexuality was still illegal and this supressed side of him may have contributed to his depression.

Whatever the deeper reasons for his suicide, Harris’s work was always full of energy and fun – his later work perhaps even more than his earlier images. He completed five full-page blocks for each book of Joseph Andrews (1952) with 16 smaller images throughout the text. Each sets the action in detailed depictions of interiors or rural landscapes. According to Brett, the image of the child being rescued from the river “gleams with an after-rainy evening light on the tree trunk, on the water and on the shoulders and limbs of the rescuer” in a way “that recalls Ravillious and Gwenda Morgan”.

Harris then did eight large engravings for Euphormio’s Satyricon (1954) for the Golden Cockerel Press, plus six small engravings for the title page, colophon and chapter heads. Harris was apparently unhappy with the printing that over-emphasised the darkness of the engravings, but the four engravings of night scenes are spectacular and darkly rich.

While completing Euphormio’s Satyricon, Harris was also illustrating Humphrey Clinker(1955) which is written entirely in letters. This may have been too much to take on. He produced 11 oval engravings framed in blue, but Brett comments that, although the book is hilarious, the world in the images fails to pick up this lightness and that the printing is coarser and less sympathetic that that of the Satyricon.

In the following five years, Harris engraved 12 still lives for the ICI Calendar of British Crafts and then embarked on Tom Jones in 1958(published in 1959). This was printed on better paper than Joseph Andrews or Humphrey Clinker and his 30 small images are bright and clear. It also had a lovely double-page title image.

According to Brett: “Tom Jones was clearly his most important achievement to date. This was a large project and would not have been the occasion for a one-man show if Derrick had felt it to be a tight corner or artistic dead-end. Hindsight lends significance to tis highly resolved style and to the sense in which the characters of this picaresque tale are ciphers, in the graphic shorthand with which Derrick set them down, yet a wealth of characterisation is contained within this shorthand and is presented with absolute immediacy.”

1n 1959, Harris saw the publication of his illustrations for Epigrams by Balzac for the Peter Pauper Press in the USA. This was a small gift book and the images benefit from being printed on a square of bright yellow. It was a new departure in style of book design and the way in which illustrators interacted with publishers, which was not really seen in the UK until Brian Wildsmith published his ABC in 1962.

In his book Mr Derrick Harris (Fleece Press, 1998) Brett writes: “Derrick Harris was, quite simple inimitable. There is no one like him, no one who has put such a crisp and graphic signature upon everything he touched.”